| Levinson

for Northeast Pennsylvania 2022 |

||

| Manufacturing isn't Everything;

It's the Only Thing The $15 an Hour Minimum Wage

Labor Relations and Unions |

This web site's purpose is to

explore the viability of running for the 8th Congressional District in

Northeast Pennsylvania in the November 2022 election. No campaign

donations are currently being solicited or accepted. Manufacturing isn't Everything; It's the Only Thing The loss or absence of manufacturing capability has always been a

leading indicator of national decline. There have been no

historical exceptions.

The $15

an Hour Minimum Wage; What Would Henry Ford Do? Ford would almost certainly figure out how to pay $25 or more

an hour while reducing prices and increasing profits in the bargain.

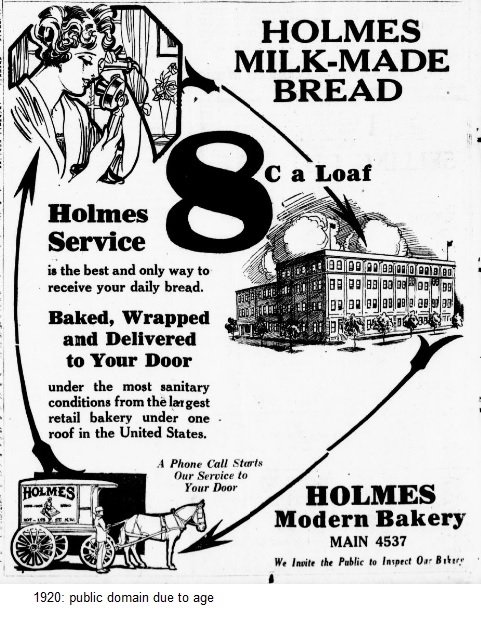

This is not speculation; he figured out how to pay $5 a day, and later

$6 and $8 a day, when the dollars were made of silver and a dime would

buy a large loaf of bread. There was a time when one blue collar worker

could support an entire family, and own a home and automobile, on a

single income, and nothing says we cannot use Ford's proven principles

to achieve similar prosperity today. Here is Ford's $5 a day minimum

wage in perspective; the ad is from 1920.

Ford's system is much more familiar today as the Toyota production system

because the three people who knew how Ford's system really

worked--Henry and Edsel Ford, and Ford's production chief Charles

Sorensen--were incapacitated, died, and retired respectuvely during the

early 1940s. The

United States forgot Ford's principles for roughly 60 years; I

rediscovered them after I read Stuelpnagel, T. R. 1993.

"Déjà Vu: TQM Returns to Detroit and Elsewhere." (Quality Progress (September),

91-95). "One Japanese executive referred repeatedly to 'the book.' When

Ford executives asked about the book, he responded: 'It's Henry Ford's

book of course—your company's book.'" That got my interest immediately.

Then I discovered the Advanced

Book Exchange in about 2000 and ordered Ford's My Life and Work. The first few

pages were a terrific revelation, and the rest proved that the Toyota

production system did in fact originate at the Ford Motor Company

during the first quarter of the 20th century. I subsequently purchased

and read Ford's other books (Today

and Tomorrow, and Moving

Forward) as well as books about Ford; one spoke of hundred-fold

productivity improvements circa 1915. Ford left the United

States an inheritance worth tens of trillions of dollars in terms of

knowledge, and it is ours to claim whenever we want. This leads us to what I believe should be the principal issue

in the 2022 election: how do we connect

Northeast PA's workers with high-wage jobs? I believe reasonably, based on what I have seen of numerous

21st century jobs (including jobs in which subminimum-wage farm workers

bend over to pick crops) and also the actual achievement of Ford and

his contemporaries, that modern jobs should

start at upward of $20 an hour. This is not however something

that politicians can legislate, but rather something that science and

engineering achieved in the past and can easily achieve again. If the

government mandates that jobs must pay $15 an hour, the same way

Shakespeare's Jack Cade declared that seven half-penny loaves of bread

would sell for a penny, one of two things will happen:

Henry Ford, however, told us in one sentence everything that

anybody needs to know about industrial and labor relations (My Life and Work, 1922): "It ought to be the

employer's ambition, as leader, to pay better wages than any similar

line of business, and it ought to be the workman's ambition to make

this possible." The principle that changed the entire world some

time around 1908, the day the first Model T rolled off Ford's moving

assembly line, is that most jobs contain

enormous amounts of built-in waste, and removal of this waste allows

higher wages, higher profits, and lower prices simultaneously.

Frank Gilbreth proved that brick laying, as practiced for thousands of

years, wasted 64% of the mason's labor by forcing him to bend over to

pick up each brick instead of having the bricks delivered at waist

level--and, as I said above, there are photos and videos today of

poorly-paid migrant workers bending over to pick the same fruits and

vegetables that sell for inflated prices while the farm owners get

mediocre profits in the bargain. Harrington Emerson described in 1911 how the Suez Canal was

dug by women who used their hands to excavate the soil and carry it

away in baskets. It came as no surprise that the workers were given

only subsistence (they were effectively forced labor, the French corvee

or corresponding Central European robota, from which the word "robot"

came) while the canal cost $80 million rather than the budgeted $30

million. Everybody

pays for bad job design; workers get low wages, customers pay high

prices, and investors realize mediocre, if any, profits. The

next time you see somebody using a mop instead of a machine to clean a

huge floor, or bending over and/or walking to do a job, that is exactly

why his or her wages are low and the product of his work overpriced. The politicians who promise a $15 an hour minimum wage can no

more deliver on that than Jack Cade would have been able to deliver

seven half-penny loaves of bread for a penny, but industrialists can

deliver $20 an hour wages. Some, in Pennsylvania's gas drilling

industry, pay upward of $25 an hour. I believe the Federal government,

and also state departments of labor and industry, should educate all

stakeholders (Labor, Capital, and Customers) on how to make this

happen. Ford's detractors will be quick to point out the company's

labor relations problems in the late 1930s including the Battle of the

Overpass in which labor organizers were beaten up by Ford's security

force. These problems happened not because the people who were running

the company at the time used Ford's principles, but because they went

against them. Upton Sinclair's pro-labor (and United

Autoworkers-endorsed) The Flivver

King proves that the company's management went against Ford's

principles including

a no-layoff policy. "Twenty men who had

been making a certain part would see a new machine brought in and set

up, and one of them would be taught to operate it and do the work of

the twenty. The other nineteen wouldn't be fired right away—there appeared to be a

rule against that. The foreman would put them at other work, and

presently he would start to "ride" them, and the men would know exactly

what that meant."

Ford had a no-layoff rule because he knew that, the instant you lay people off when productivity improves, the workforce will not support further productivity improvements. Frederick Winslow Taylor said the same thing in Principles of Scientific Management (1911) as did Ford himself (My Life and Work). When Ford was in charge, his workers not only had no desire to unionize, they turned against their own union when it called on them to strike. "In England we did

meet the trades union question squarely in our Manchester plant. The

workmen of Manchester are mostly unionized, and the usual English union

restrictions upon output prevail. We took over a body plant in which

were a number of union carpenters. At once the union officers asked to

see our executives and arrange terms. We deal only with our own

employees and never with outside representatives, so our people refused

to see the union officials. Thereupon they called the carpenters out on

strike. The carpenters would not strike and were expelled from the

union. Then the expelled men brought suit against the union for their

share of the benefit fund. I do not know how the litigation

turned out, but that was the end of interference by trades union

officers with our operations in England." (My Life and Work, 1922)

Ford knew how to break up a union; pay the workers as much rather than as little as possible, and then the workers will look for ways to make their jobs even more productive because they know a fair share of the improvements will show up in their pay envelopes. Ford acknowledged that unions are necessary when employers look for ways to pay their people as little as possible. We got the United Mine Workers because mine bosses looked for ways to pay coal miners as little as possible and then cheat them of those wages in company stores as depicted accurately in The Molly Maguires. When the employer looks for ways to cut wages and benefits, or ship jobs offshore, while the CEO rakes in millions of dollars in salary and bonuses, the employer does not deserve the respect, trust, and loyalty of its workforce. Ford made it emphatically clear (My Life and Work) that such a CEO was unfit for his job and the best way for the company to cut expenses would be to fire that CEO for incompetence rather than lay off workers and/or ship jobs offshore. "Cutting wages is the

easiest and most slovenly way to handle the situation, not to speak of

its being an inhuman way. It is, in effect, throwing upon labour

the incompetency of the managers of the business."

I also know, however, of organizations in which the CEO or owner cut his own pay to nothing during hard times, at which point workers were willing to accept small pay cuts to keep the organization in business. Bill "at" levinson4nepa.com PRIVACY NOTICE: This

Web domain, with the exception of the blog (Wordpress, not yet set up)

does not use

cookies. If we can figure out how to disable cookies for the blog, we

will, as we do not want to collect personal information. There is an automatic

cookie deleter for Firefox (it may also be available for Chrome and

Edge)

that removes all cookies except those from domains you authorize (safe

list) to put them on your computer. |